what natural tbi h can you use to stain hardwood floors

- Research

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Mild traumatic brain injury induces microvascular injury and accelerates Alzheimer-like pathogenesis in mice

Acta Neuropathologica Communications volume 9, Article number:74 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is considered as the most robust environmental take chances factor for Alzheimer's illness (Advert). Likewise directly neuronal injury and neuroinflammation, vascular impairment is also a hallmark event of the pathological cascade later on TBI. Still, the vascular connection between TBI and subsequent Advert pathogenesis remains underexplored.

Methods

In a closed-head mild TBI (mTBI) model in mice with controlled cortical impact, we examined the time courses of microvascular injury, blood–brain bulwark (BBB) dysfunction, gliosis and motor function damage in wild blazon C57BL/6 mice. We too evaluated the BBB integrity, amyloid pathology too as cognitive functions after mTBI in the 5xFAD mouse model of AD.

Results

mTBI induced microvascular injury with BBB breakdown, pericyte loss, basement membrane alteration and cerebral blood menstruation reduction in mice, in which BBB breakdown preceded gliosis. More than chiefly, mTBI accelerated BBB leakage, amyloid pathology and cognitive impairment in the 5xFAD mice.

Discussion

Our data demonstrated that microvascular injury plays a key role in the pathogenesis of AD after mTBI. Therefore, restoring vascular functions might be beneficial for patients with mTBI, and potentially reduce the risk of developing Advertising.

Groundwork

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an age-related progressive neurodegenerative condition, manifesting amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle formation, neurovascular and neuroimmune dysfunctions, and cognitive impairment [ane]. While advanced aging increases the likelihood of AD, genetic inheritance and ecology risk factors too contribute significantly [2]. For example, Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is considered as the most robust ecology risk factor for AD [3]. TBI is a leading crusade of death and disability, specially in young adults, resulting in a great impact on productivity and dependence on health care in later life [4]. Both clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that TBI triggers multiple neurodegenerative cascades, including axonal and dendritic impairment, excitatory toxicity, neuroinflammation and prison cell death [five], also equally cerebrovascular impairment such as edema, circulatory insufficiency, and blood–encephalon barrier (BBB) breakdown [6], exhibiting a high similarity with Advert [4]. TBI is highly prevalent during military service and contact sports, and doubles the hazard of developing AD and dementia [7]. More chiefly, it also exacerbates certain pathological events that are specific to AD, including the brain's overproduction and aggregating of β-amyloid (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyperphosphorylated Tau [8, 9]. Notwithstanding the underlying mechanisms remain elusive.

Histological and neuroimaging assessments have demonstrated that microvascular injury with BBB breakdown are common in TBI patients. It occurs during the acute/subacute phase of TBI [ten, 11] and may last for years in nearly fifty% of the survivors [12, 13], resulting in long-term brain dysfunctions. Such microvascular endophenotype was well recapitulated in animal models of TBI [four], including fluid percussion injury, controlled cortical impact and blast injury. Mechanistically, TBI induces endothelial dysfunction [xiv], disrupts the crosstalk between endothelial cells and pericytes [fifteen], reduces cognitive claret flow (CBF) and causes tissue hypoxia [16], upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and metallopeptidases [17, eighteen], leukocyte infiltration [19], gliosis and neuroinflammation [5], which all contribute to BBB dysfunctions.

As the interface betwixt the circulation and primal nervous system (CNS), the BBB plays a key function in normal brain physiological regulation and homeostasis [20]. Microvascular injury often results in a cascade of events including extravasation of plasma proteins that are potentially toxic to neuronal cells, parenchymal edema and hypoxia, metabolic stress including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondrial stress, accumulation of metabolic wastes, activation of microglia and astrocytes, and somewhen neuronal dysfunctions [20, 21]. Although microvascular injury is a shared endophenotype between TBI and Ad [four], and a strong modifier of AD pathogenesis and progression [21], the vascular link between TBI and AD has not been investigated in depth.

Since balmy TBI (mTBI) represents near 85% of cases, we applied a shut-head mTBI model in rodents to investigate vascular impairment after mTBI, as well every bit to understand its link to AD pathogenesis. We institute that mTBI induced microvascular injury and BBB dysfunction in the acute/subacute stage afterwards injury, which was tightly associated with circulatory insufficiency and pericyte loss, and in full general preceded astrogliosis and microglia activation. In addition, applying mTBI in 5xFAD transgenic model of Advertizing demonstrated that mTBI accelerated BBB disruption, amyloid pathology and cognitive impairments. Therefore, improving vascular functions and BBB integrity in patients with mTBI may exist beneficial and even reduce the risk of developing AD.

Methods

Animals

12–16 weeks erstwhile C57BL/vi mice and 5xFAD mice were used (Additional File one: Fig. 1A). 5xFAD mouse model is a well-characterized mouse model of AD, with expression of human APP and PSEN1 transgenes with a total of 5 Ad-linked mutations: the Swedish (K670N/M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) mutations in APP, and the M146L and L286V mutations in PSEN1 [22]. All procedures are canonical by the Institutional Brute Care and Employ Committee at the University of Southern California using the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

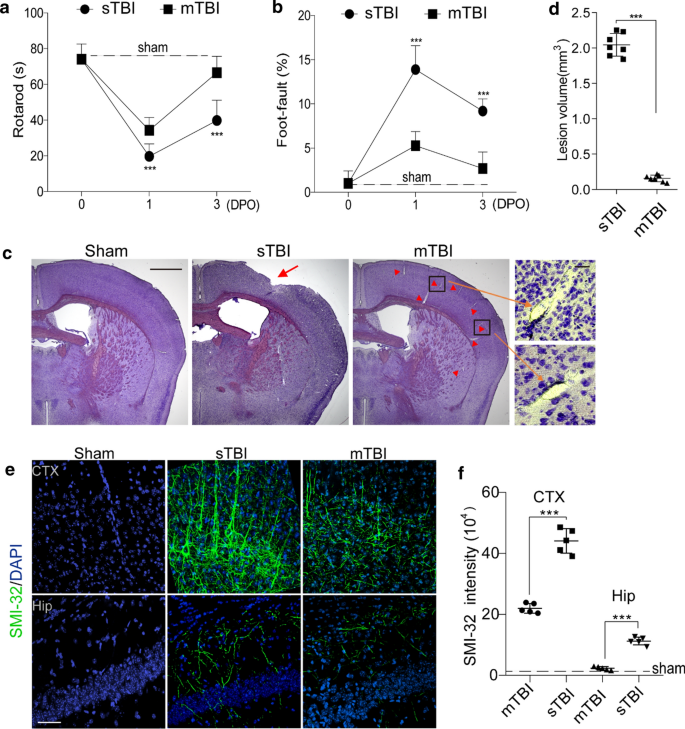

Traumatic brain injury models with controlled cortical bear upon in mice. a–b Rotarod examination (a) and foot-mistake test (b) were performed on 0, ane day and 3 days post operation (DPO) in sTBI mice (due north = 8) or mTBI mice (n = 7). Nuance lines indicate average value from sham-operated group (northward = 5). In a–b mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001 between sTBI and mTBI groups; NS, non-meaning (P > 0.05), one-style ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's postal service-hoc tests. c Representative images of cresyl violet staining of encephalon sections from sham-operated, sTBI and mTBI mice. Calibration bar = 1 mm (left), and 50 µm (right) in high magnification. Pointer indicates cortical lesion; arrowhead indicates enlarged perivascular space. d Quantification of TBI-induced lesion book at 24 h post-injury in sTBI mice and mTBI mice. The injury resulted in a significantly larger lesion volume in sTBI mice when compared with mTBI mice. northward = 7 mice per grouping. e–f Representative images e of fluorescence immunostaining for SMI-32 (green) and DAPI (bluish), quantification of SIM-32 fluorescence intensity f in cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (Hip) of sham-operated, sTBI and mTBI mice 3 days later on injury. Scale bar = 50 µm, n = 5 mice in sham-operated, sTBI and mTBI group respectively. In d, f, Mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001 past Student'southward t-test

Randomization and blinding

All animals were randomized for their genotype data and surgical procedures, and included in the analysis. The operators responsible for the experimental procedures and data assay were blinded and unaware of group allocation throughout the experiments.

Closed-head mTBI mouse model

Mice received a balmy closed-caput impact following the procedures previously reported with minor modifications [23]. Briefly, for a precise impact mimicking mTBI, we utilized a stereotactic frame with adaptable angle (Stereotaxic Alignment System, KOPF) to ensure the impacted surface (the impact central bespeak at Bregma − 2 mm and lateral two.5 mm) of the skull was presented perpendicular to the impactor (Additional File ane: Fig. 1b, Brain and Spinal Cord Impactor, #68099, RWD Life Science). We besides custom-fabricated plastic flat-tip impactor (RWD Life Science) to reduce the affect. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (90 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg; i.p.), then the head was fixed with a 15° angle, and a gel pad was placed nether the head in lodge to maximally avoid the skull fractures and intracerebral bleeding. An incision was made to expose skull surface after anesthesia and and then the mice were subjected to an impact using a 4 mm plastic flat-tip impactor. The velocity was 3 m/s, the depth was 1.0 mm and the bear upon elapsing was 180 ms (come across Additional File one: Fig. 1c–d). Afterward the procedure, the mice were put back to their cages with heating to recover from the anesthesia. For sham-operated mice, the aforementioned procedure was performed as the mTBI group except the tip was set ii.0 mm above the skull.

Open-head severe TBI (sTBI) mouse model

Mice received the sTBI following the procedures previously reported [24]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (xc mg/kg, 9 mg/kg; i.p.), and the mouse head was then stock-still in the stereotactic frame (Stereotaxic Alignment System, KOPF). A craniotomy was made using a drill and 4.v-mm trephine in the center betwixt Lambda and Bregma, and then the bone flap was removed. Mice were subjected to an touch using a 4 mm metallic apartment-tip impactor (Encephalon and Spinal String Impactor, #68099, RWD Life Scientific discipline). The impact central point was Bregma − 2.five mm and lateral ii.5 mm. The velocity was 3 thou/southward, the depth was 1 mm and the touch duration was 180 ms. Then the scalp was airtight with suture, and the mice were put back to their cages to recover from the anesthesia. For sham-operated mice, the same procedure was performed as the sTBI grouping except the tip was ready 2.0 mm above the skull.

Behavioral tests

Rotarod test

Mice were trained on an accelerating (v–20 rpm) rotating rod (rotarod) for iii days before TBI. Test sessions consist of six trials at a variable speed (an initial velocity of v rpm was used for the first 10 s, a linear increase from five to x rpm for the next 30 s, and a linear increase from x to 20 rpm between forty and 80 s). The final score was determined every bit the mean time that a mouse was able to remain on the rod over half-dozen trials.

Human foot mistake test

The human foot-error test was performed as previously described [25]. Mice were placed on hexagonal grids of dissimilar sizes. Mice placed their paws on the wire while moving along the grid. With each weight-bearing stride, the paw may fall or slip between the wire. This was recorded as a foot mistake. The total number of steps (move of each forelimb) that the mouse used to cross the grid was counted, and the total number of foot faults for each forelimb was recorded.

Contextual fearfulness workout

A hippocampus-dependent fearfulness conditioning test was performed equally previously described [26]. The experiments were performed using standard workout chambers housed in a soundproof isolation cubicle and equipped with a stainless-steel grid floor connected to a solid-state shock scrambler. The scrambler was connected to an electronic constant-current stupor source that was controlled via Freezeframe software (Coulbourne Instruments). A digital camera was mounted on the steel ceiling and behavior was monitored. During grooming, mice were placed in the conditioning bedchamber for 4 min and received ii-foot shocks (0.25 mA, 2 southward) at one-min interval starting two min after placing the mouse in the sleeping room. Contextual memory was tested the next day in the bedroom without human foot shocks. Hippocampus-dependent fear retentiveness germination was evaluated past scoring freezing behavior (the absence of all move except for respiration). For the contextual fright conditioning paradigms, the automated Freezeframe arrangement was used to score the per centum of total freezing time with a threshold set at ten% and minimal bout duration of 0.25 due south.

Determination of lesion volume

Mouse brains were cutting into series 20 µm cryostat sections. Every tenth section was stained with cresyl violet and the lesion surface area was determined using the Image J analysis software. Sections were digitized and converted to gray scale, and the border between TBI and non-TBI tissue was outlined. The lesion volume was calculated past subtracting the volume of the non-lesioned area in the ipsilateral hemisphere from the volume of the whole area in the contralateral hemisphere and expressed in mm3 every bit previously described [27].

Assessment of edema

Brain water content is a sensitive mensurate of cognitive edema which was adamant using the wet/dry method as previously described [27]. Mice were decapitated and brains were quickly removed from the skull. The fresh encephalon was weighed in 3 mm coronal sections of the ipsilateral cortex, centered upon the impact site, then dehydrated for 24 h at 110 °C and reweighed. The percentage of encephalon h2o content was calculated using the following formula: (moisture weight − dry weight)/(wet weight) × 100.

Tracer injection to observe BBB leakage

Mice were injected via the tail vein with Alexa Fluor 555-cadaverine (6 µg/thousand; Invitrogen, A30677) [28] dissolved in saline i, 3 and 8 days after mTBI. Subsequently 2 h mice were anesthetized and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, and the brains were nerveless.

Evaluation of BBB permeability

BBB permeability was assessed by measuring the extravasation of Evans Blue dye every bit described previously [29]. 24 h after TBI injury, the mice were anesthetized, and Evans Bluish dye (two% in saline) was injected slowly through the jugular vein (four mL/kg) and allowed to broadcast for one.5 h before sacrifice.

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI)

LSCI is based on the blurring of interference patterns of scattered laser light by the menses of claret cells to visualize claret perfusion in the microcirculation instantaneously [30]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with gas anesthesia (isoflurane 2% in oxygen), with the head fixed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments) and placed under an RFLSI Pro (RWD life sciences) and maintained at 1.2% isoflurane throughout the experiment. The surface of the skull is illuminated with a 784-nm 32-mW light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation (RWD life science) at a thirty° angle with a beam expander and light intensity controlled by a polarizer. Claret flow is detected by a CCD camera and the prototype acquisition is performed using custom software (RWD life scientific discipline). 3 hundred frames are caused at x Hz with ten-ms exposure time. For the cess of speckle contrast over fourth dimension, regions of interest (ROIs) were selected and centered at the site where the laser is targeted on the cortex.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy analysis

At endpoint, mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with PBS, and mouse brains were extracted and fixed for 12 h in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at four °C. 20 µm-thick coronal cryosections were used for immunohistochemistry in this written report. After washing with PBS, encephalon sections were permeabilized and incubated in 5% Donkey Serum for ane h for blocking. Then the brain tissues were incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibiotic information is as following: anti-Fibrinogen antibody (1:200, Dako, A0080), anti-Iba1 antibiotic (1:500, Wako, 019-19741), anti-NeuN antibody (ane:200, Abcam, ab177487), anti-Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:200, Invitrogen, 13-0300), anti-SMI-32 antibody (one:thou, Biolegend, 801709), anti-Cluster of differentiation (CD13) antibody (1:200, R&D Systems, AF2335), anti-β amyloid antibiotic (1:200, #D54D2, Cell Signaling). Later on washing off the primary antibody with PBS, the brain sections were so incubated with secondary antibodies (one:500; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) for i h at room temperature. Dylight 488 conjugated-lectin (1:200, Vector, DL1174) was used to label brain vasculature, and Alexa Fluor 647 Ass anti-Mouse IgG (ane:500; Invitrogen, A-31571) was used to detect extravasation of IgG. Later that, the sections were rinsed with PBS and covered with fluorescence mounting medium with DAPI (4′,half-dozen-diamidino-ii-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories, #H-1200).

Detection of apoptosis

TUNEL analysis was performed co-ordinate to the manufacturer'south protocol (CAS7791-13-1, Roche). Tissues were incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture in a humidified sleeping room for 30 min at 37 °C in the nighttime.

Detection of Aβ plaques

Later PFA fixation, the sections were incubated in 1% aqueous Thioflavin S (T1892; Sigma) for five min and rinsed in 80% ethanol, 95% ethanol, and distilled water. All images were taken with the Nikon A1R confocal microscopy and analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. In each beast, 4 randomly selected fields in the cortex and hippocampus in TBI-afflicted hemisphere were analyzed in 4 non-adjacent sections (~ 100 µm autonomously) and averaged per mouse.

Cresyl violet staining

The encephalon tissue sections were firstly fixed by methanol for v min, and then stained with the Cresyl Echt Violet staining kit (American MasterTech, catalog # AHC0443) and incubated for 5 min; adjacent, the slides were rinsed in 2 changes of distilled water (fifteen due south each) to remove the excess stain; and then the slides were rinsed using 100% ethanol (10 s). At last, the slides were coverslipped with mounting medium.

Extravascular IgG, fibrinogen and fibrin deposits

We used antibodies that detected IgG, fibrinogen and fibrinogen-derived fibrin polymers (run across Immunohistochemistry). Ten-micron maximum projection z-stacks were reconstructed, and the IgG, fibrinogen and fibrin-positive perivascular signals on the abluminal side of lectin-positive endothelial profiles on microvessels ≤ 6 µm in diameter were analyzed using ImageJ. In each animal, 4–five randomly selected fields in the cortex in both mTBI-affected hemisphere and unaffected contralateral hemisphere were analyzed in iv not-next sections (~ 100 µm autonomously) and averaged per mouse.

Assay for SMI-32

Ten-micron maximum project z-stacks were reconstructed, and the SMI-32 signals were analyzed using ImageJ. In each animal, 4 randomly selected fields in the cortex and hippocampus in TBI-affected hemisphere were analyzed in 4 non-adjacent sections (~ 100 µm autonomously) and averaged per mouse.

GFAP-positive astrocytes and Iba1-positive microglia counting

For quantification, GFAP-positive astrocytes or Iba1-positive microglia that besides co-localized with DAPI-positive nuclei were quantified by using the Image J Cell Counter analysis tool. In each animal v randomly selected fields from the cortex were analyzed in four nonadjacent sections (~ 100 µm apart). The number of GFAP-positive astrocytes was expressed per mmii of brain tissue. The activated microglia undergo morphological changes including retraction of the processes and acquisition of a phagocytotic shape, just the quiescent microglia exhibit a ramified morphology [31].

NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei counting

For quantification, NeuN-positive neurons were quantified by using the Image J Cell Counter analysis tool. In each fauna, 5 randomly selected fields from the cortex were analyzed in 4 nonadjacent sections (~ 100 µm apart). The number of NeuN-positive neurons colocalized with TUNEL was counted followed past the same procedure.

Quantification of pericyte numbers and coverage

The quantification analysis of pericyte numbers and coverage was restricted to CD13-positive perivascular landscape cells that were associated with brain capillaries divers as vessels with ≤ 6 µm in diameter. For pericyte numbers, ten-micron maximum project z-stacks were reconstructed, and the number of CD13-positive perivascular cell bodies that co-localized with DAPI-positive nuclei on the abluminal side of lectin-positive endothelium on vessels ≤ 6 µm counted using ImageJ Cell Counter plug-in. In each animal, 4–five randomly selected fields in the cortex regions were analyzed in four non-adjacent sections (~ 100 µm autonomously) and averaged per mouse. The number of pericytes was expressed per mmii of tissue. For pericyte coverage, ten-micron maximum projection z-stacks were reconstructed, and the areas occupied by CD13-positive (pericyte) and lectin-positive (endothelium) fluorescent signals on vessels ≤ 6 µm were subjected separately to threshold processing and analyzed using ImageJ equally previously described [32]. In each brute, iv–five randomly selected fields in the cortex regions were analyzed in 4 nonadjacent sections (~ 100 µm apart) and averaged per mouse.

Microvascular capillary length

Ten-micron maximum projection z-stacks were reconstructed, and the length of lectin-positive capillary profiles (≤ 6 µm in diameter) was measured using the ImageJ plugin "Neuro J" length analysis tool. In each animal, 4–5 randomly selected fields in the cortex were analyzed from 4 nonadjacent sections (~ 100 µm apart) and averaged per mouse. The length was expressed in mm of lectin-positive vascular profiles per mmiii of brain tissue.

Aβ deposits calculation

Aβ-positive areas were determined using ImageJ software. Briefly, the images were taken on a BZ9000 fluorescent microscope in single manifestly at twenty× and subjected to threshold processing (Otsu) using ImageJ, and the pct area occupied by the signal in the image area was measured as described previously [26]. In each animal, four randomly selected fields from the cortex and hippocampus were imaged and analyzed in four nonadjacent sections (~ 100 µm autonomously).

Western absorb

The total proteins from cortical tissue of TBI-affected hemisphere in sham-operated, sTBI and mTBI mice were extracted, and Synapsin I was analyzed by Western absorb. Briefly, protein samples were separated past electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific bounden sites were blocked in TBS, overnight at 4 °C, with 2% BSA and 0.one% Tween-20. Membranes were rinsed for ten min in a buffer (0.1% Tween-20 in TBS) and so incubated with anti-synapsin I (1:1500, Sigma) followed by anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Afterward rinsing with buffer, the immunocomplexes were developed with Thou:BOX Chemi XX6 gel doc system (Syngene) and analyzed in Image Lab software. β-Actin was used as an internal control for Western blot.

Statistical analysis

Sample sizes were calculated using nQUERY assuming a two-sided alpha-level of 0.05, 80% power, and homogeneous variances for the 2 samples to be compared, with the means and common standard difference for different parameters predicted from published data and airplane pilot studies. For comparison between two groups, the F examination was conducted to determine the similarity in the variances between the groups that are statistically compared, and statistical significance was analyzed by Student'due south t-test. For multiple comparisons, Bartlett'southward test for equal variances was used to determine the variances betwixt the multiple groups and one-mode analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test was used to test statistical significance. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software by an investigator blinded to the experimental conditions. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically meaning.

Results

Microvascular injury in a mouse model of mTBI

To decide the vascular impairment in mTBI, we first compared the pathological changes and functional performances in an open-head astringent TBI (sTBI) model with a close-caput mTBI model, based on controlled cortical impact (Additional File one: Fig. 1). Consistent with previous studies [33], the sTBI model induced stiff deficits in motor function, as seen on both rotarod examination and foot-fault test (Fig. 1a, b); whereas the mTBI model only induced transient motor impairments, as the mice well-nigh recovered in 3 days in the same behavioral tests (Fig. 1a, b). In line with the behavioral outcomes, mTBI model didn't cause prominent cortical lesion at 24 h post-injury, when compared to the sTBI model with an average lesion volume of over ii mm3 (Fig. 1c, d). Brain water content, as a measure of cognitive edema, was non significantly changed 24 h after mTBI either (Additional File 1: Fig. 2a). In add-on, we observed very few TUNEL- and NeuN- double-positive cells in the mTBI impacted ipsilateral cortex at 3 days after mTBI (Boosted File one: Fig. 2b–c); while ~ twenty% neuronal expiry was found well-nigh the cortical lesion in the sTBI model (Additional File one: Fig. 2b–c).

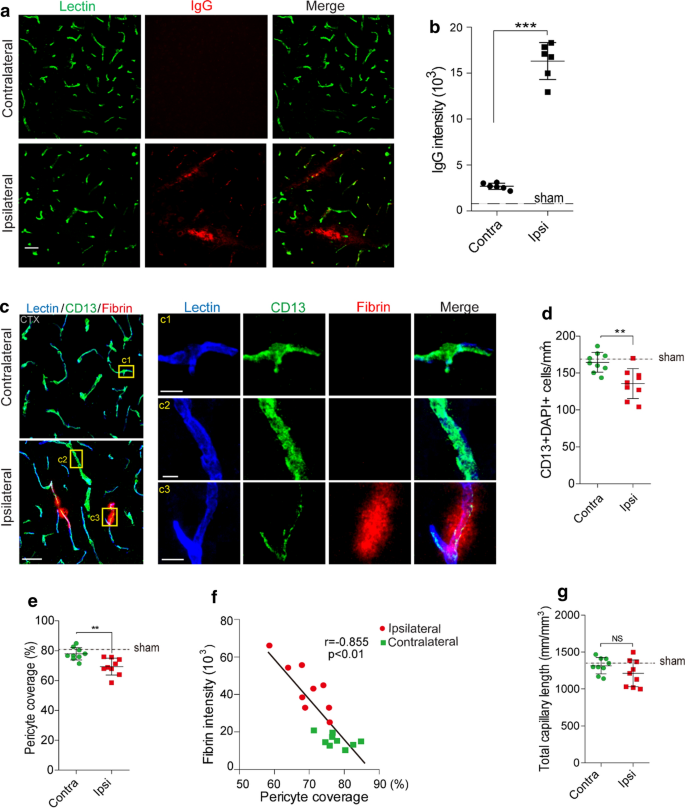

Altered pericyte coverage in mTBI mice. a–b Representative images (a) and quantification (b) showing extravasation of plasma IgG (red) in brain parenchyma 3 days after mTBI. northward = 6 mice. Dash line indicates an average value from sham-operated group (north = 5 mice). Scale bar = 50 µm. c Representative images showing CD13-positive pericyte coverage (green), lectin-positive endothelial vascular profiles (blue) and extravasation of fibrin deposits (scarlet) in brain parenchyma of mTBI-affected ipsilateral side or contralateral side 3 days later on mTBI. Scale bar = 50 µm. Insert on right: high magnification images of boxed regions in (c1–c3), Scale bar = x µm. d–east Quantification of CD13-positive pericyte cell bodies per mm2 (d) and pericyte coverage on lectin microvessel profiles (e) in brain parenchyma of mTBI-affected ipsilateral side and contralateral side three days after mTBI. n = 9 mice per group. f Pearson's correlation plot between BBB impairment based on fibrin deposits and loss of pericyte coverage in brain parenchyma iii days after mTBI. n = eighteen hemispheres. r = Pearson'south coefficient. P, significance. one thousand Quantification of microvascular density in the cortexes of mTBI-afflicted ipsilateral side and contralateral side three days subsequently mTBI. n = 9 mice per group. Mean ± SD in b, d–e, g; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not-significant (P > 0.05) past Student's t-test

Interestingly, axonal injury was detectable 3 days subsequently mTBI in both mTBI-affected ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 1e), based on a monoclonal SMI-32 antibody confronting non-phosphorylated neurofilament [34], although to a much lesser extent than that constitute in sTBI (Fig. 1e, f). Western blotting of synaptic marking synapsin I also showed a ~ 32% reduction in mTBI-affected ipsilateral cortex, compared to a 75% reduction afterward sTBI (Additional File 1: Fig. 2d–east). Microglia and astrocytes were much less activated in both mTBI-affected ipsilateral cortical areas and contralateral area, when compared with sTBI-affected ones (Additional File 1: Fig. iii). Dissimilar sTBI, the microglial activation and astrogliosis did not spread much to the contralateral hemisphere at iii days after mTBI (Additional File 1: Fig. 3b, d).

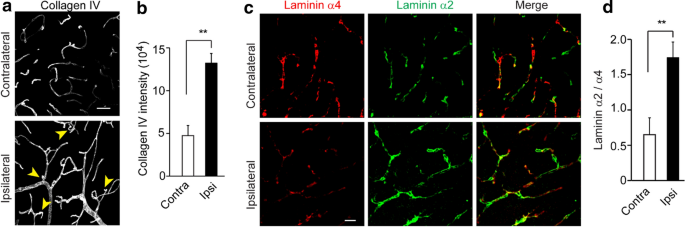

Basement membrane structural change in mTBI mice. a–b Representative confocal microscope images (a) and quantification (b) showing upregulation of collagen IV in mTBI-impacted ipsilateral cortical area 3 days after mTBI compare to contralateral side. Calibration bar = 50 µm. c Representative confocal microscope images showing differential laminin α2 and α4 levels in mTBI-impacted ipsilateral cortical area and contralateral side iii days after mTBI. d Quantification of α2 and α4 ratio based on fluorescent intensities in mTBI-impacted ipsilateral cortical surface area compare to contralateral side. Scale bar = 30 µm. n = half dozen mice per group. Mean ± SD in b, d; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, non-pregnant (P > 0.05) past Pupil's t-test

BBB breakdown is a hallmark of TBI, which occurs acutely within hours after tissue damage and lasts for days [35]. Every bit cresyl violet staining showed vascular segments with morphological impairment in brain sections from mTBI mice (Fig. 1c, arrowheads and inserts), we next performed histological analysis to examine the microvascular injury and BBB dysfunction occurred in the acute/subacute phase of mTBI. Immunostaining for plasma-derived IgG (Fig. 2a) demonstrated a ~ sixfold increase in perivascular IgG deposits in the mTBI impacted cortical surface area 3 days later mTBI (Fig. 2b). We as well found like results in extravascular fibrin deposits (Additional File 1: Fig. 4a, b), or extravasation of exogenous tracer 555-cadaverine [28] (Boosted File i: Fig. 4c–d), suggesting BBB is compromised afterward mTBI, which is consistent with findings in human being patients and different animal models [vi].

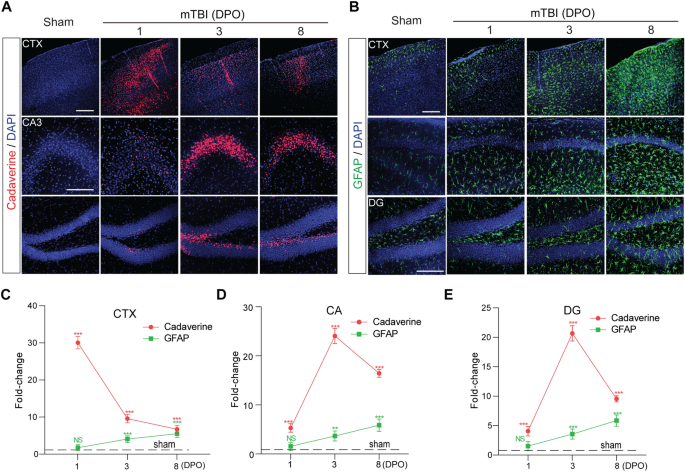

The time courses of BBB dysfunction and astrogliosis after mTBI in mice. a Representative confocal microscope images showing the extravasation of intravenously administrated Alexa-555 cadaverine (ruby-red) in cortex (CTX), Cornu Ammonis iii (CA3) and dentate gyrus (DG) surface area i-twenty-four hour period, 3- and 8- days post operation (DPO). Calibration bar = 100 µm. b Representative confocal microscope images showing GFAP-positive astrocytes (greenish) in cortex (CTX), CA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) area 1-day, 3- and viii- days postal service operation (DPO). Scale bar = 100 µm. c–e Quantification for the fold changes for cadaverine intensity (n = five mice per time point) and GFAP positive cells (n = v mice per fourth dimension point) in CTX area, CA surface area and DG surface area 1-day, 3- and 8- days post operation (DPO). In c–e, data are presented every bit mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01 NS, non-significant (P > 0.05) compare to sham group, 1-way ANOVA followed past Bonferroni's mail service-hoc tests. Nuance lines indicate the sham-operated group

mTBI resulted in pericytes loss and basement membrane alteration

Pericytes play a key role in regulating neurovascular functions of the brain including formation and maintenance of the BBB [28]. We institute a substantial loss of encephalon pericytes based on the number of CD13-positive cells (Fig. 2c, d) in the impacted ipsilateral side 3 days after mTBI, when compared with unaffected contralateral hemisphere, also as a reduction of pericyte coverage based on CD13 profile on Lectin-positive endothelial profiles (Fig. 2e). This pericyte loss is even more evident in microvascular segment with strong fibrin deposits (Fig. 2c inserts). More chiefly, accumulation of perivascular fibrin deposits in mTBI mice correlated tightly with the reductions in pericyte coverage (Fig. 2f). However, there was no meaning change in the total capillary length between impacted ipsilateral hemisphere and unaffected contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 2g), suggesting astute vascular rarefication perchance is more than specific to moderate and severe TBI [36]. Furthermore, the pathological changes of BBB in the astute/subacute phase of mTBI was associated with microcirculation insufficiency, as LSCI showed a ~ 50% reduction in CBF in the impacted cortex 3 days afterward mTBI (Additional File 1: Fig. 4e, f).

Contempo genetic profiling studies in rodents indicated a TBI-induced genomic response in genes associated with the extracellular matrix proteins and basement membrane structures [37, 38]. We so performed histological assay for dissimilar markers of perivascular compartments and extracellular basement membrane. Collagen IV, secreted by endothelial cells, mural cells and astrocytes, is a mark for both inner and outer basement membranes in the perivascular space [39]. It was significantly increased by 2.9-fold in mTBI-affected hemisphere compared to the unaffected contralateral side of the brain (Fig. 3a, b). More interestingly, we found immunostaining for vascular laminin α4 [40] was dramatically reduced in the mTBI-affected hemisphere when compared with the unaffected contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 3c), which is consistent with vascular injury and suggests vascular compartment within the perivascular space decreased afterwards mTBI. In improver, laminin α2 immunoreactivity around the astrocytic endfeet of microvessels [41] was dramatically increased in mTBI-affected hemisphere compared to the unaffected contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 3c), indicating that the parenchymal compartment of the perivascular space increased after mTBI. Therefore, the ratio of laminins α2/α4 may potentially reflect the perivascular structural changes afterward mTBI (Fig. 3d).

mTBI induced BBB dysfunction precedes gliosis

To examine the time grade of cerebrovascular damage and BBB dysfunction in mTBI mice, we performed in vivo tracing of systemically administrated Alexa Fluor 555-cadaverine [28], on 1 24-hour interval, iii- and 8-days post performance (DPO). We found that a astringent BBB damage in the impacted cortex area at 1 DPO (Fig. 4a), earlier astrogliosis and microglial activation became substantial (Fig. 4b, Boosted File 1: Fig. 5a). More specifically, cadaverine tracer indicated a ~ 30.1-fold increment in parenchymal uptake in the ipsilateral cortex, which recovered gradually over 8 days (Fig. 4c). On the other mitt, the BBB damage in the hippocampal area appeared at i DPO, but peaked around iii DPO as indicated by ~ 24.1-fold and ~ 20.7-fold increase of uptake in CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) areas, respectively (Fig. 3d, e). On the other mitt, immunostaining for GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 4b) and Iba1-positive microglial cells (Additional File 1: Fig. 5a) indicated that astrocytes and microglial cells were significantly activated between 3 and 8 DPO after mTBI in both cortex and hippocampus (CA1 and DG) areas (Fig. 4c–eastward and Additional File 1: Fig. 5b–d), when compared with sham-operated group. Therefore, our data indicate that microvascular injury and BBB dysfunction preceded astrogliosis and microglial activation in the acute/subacute stage of mTBI.

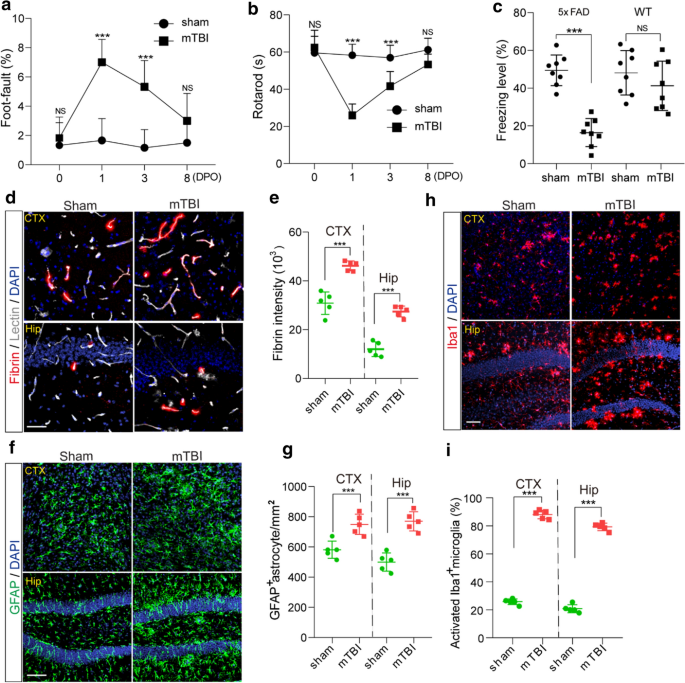

Accelerated cerebral impairment and pathologies in 5xFAD mice later on mTBI. a–b Human foot- error (A) and Rotarod (b) tests were performed in 3 months old 5xFAD mice on 0, 1, three and 8 days after mTBI or sham-operation. n = 8 mice per time point per group. c Contextual fright conditioning test was performed in three months onetime 5xFAD mice 8 days after mTBI or sham-operation as in (a–b), or in non-transgenic littermates (WT) 8 days afterward mTBI or sham-operation. due north =8 mice per group. d–e Representative images (d) and quantification (e) showing extravascular fibrin deposits in brain parenchyma 8 days afterwards mTBI, in both cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (Hip). Lectin (gray), fibrin (cerise). north = 5 mice; Scale bar = fifty µm. f–g Representative images (f) and quantification (one thousand) showing GFAP-positive astrocytes in encephalon parenchyma 8 days later mTBI. GFAP (green). n = 5 mice per group; Scale bar = fifty µm. h Representative images of fluorescence immunostaining for microglial marker Iba1 (cherry-red) and DAPI (blueish) in brain parenchyma 8 days afterwards mTBI. Scale bar = 50 µm. i Quantification for the percentage of activated Iba1 positive cells in both cortex and hippocampus (n = five mice per group). In a–b, Mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001, NS, non-significant (P > 0.05), one-mode ANOVA followed by Bonferroni'south post-hoc tests. In c, e, g, i, Mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001, NS, non-pregnant (P > 0.05) by Student's t-test

mTBI exacerbated BBB breakdown, amyloid pathologies and cognitive harm in 5xFAD mice

Prominent amyloid pathologies are found in at to the lowest degree 30% of TBI patients [42]. Next, nosotros conducted mTBI in the 5xFAD mouse model of AD at three months of historic period, where amyloid pathology is evident but cognitive function remains relatively normal [22]. Longitudinal behavioral tests in the acute/subacute phase of mTBI indicated that the 5xFAD mice had a transient damage in motor coordination at 1 DPO just before long recovered nearly dorsum to normal in eight days, as shown by rotarod and foot fault tests (Fig. 5a, b). However, these 5xFAD mice suffered essentially from cognitive impairment at viii DPO, as shown by a reduction in freezing time based on contextual fear conditioning test (Fig. 5c), when compared with sham-operated 5xFAD mice or wild type littermates (WT).

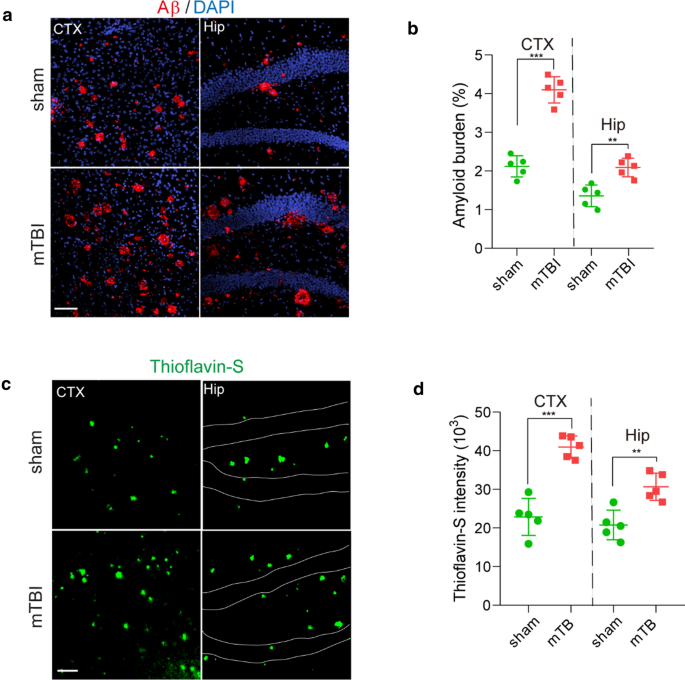

More importantly, mTBI exacerbated the BBB dysfunction in 5xFAD mice [32], as shown by > 53.3% extravascular fibrin deposits in both mTBI affected cortex and hippocampus when compared with sham-operated mice at eight DPO (Fig. 5d, eastward). Additionally, mTBI resulted in gliosis changes in cortex and hippocampus, as indicated by meaning increases in both astrocytes (Fig. 5f, thousand) and activated microglia cells at eight DPO (Fig. 5h, i). Using histological assay, we establish that the amyloid brunt in mTBI mice was nearly doubled in both cortex and hippocampus 8 days after mTBI (Fig. 6a, b), when compared with sham-operated 5xFAD mice. This is consistent with increased Thioflavin-S positive amyloid plaques (Fig. 6c, d), and demonstrates that mTBI exacerbated the amyloid pathologies in 5xFAD mice.

Accelerated amyloid pathology in 5xFAD mice after mTBI. a–b Representative images (A) showing immunostaining of brain amyloid deposits (red), DAPI (blue) and quantification (b) for the amyloid brunt (based on the percentage of cortical area occupied with Aβ immunostaining) in cortex (CTX) and Hippocampus (Hip) area 8 days post operation. due north = v mice per group, calibration bar = 100 µm. s–d Representative images (c) showing Thioflavin-Southward labelled amyloid plaques (dark-green) and quantification for the intensity of Thioflavin-S (d) in cortex (CTX) and Hippocampus (Hip) area eight days mail operation. northward = 5 mice per group, scale bar = 100 µm. In b and d, information are presented as Mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; past Student's t-test

Discussion

Microvascular injury and BBB damage are commonly establish across neurodegenerative weather, including only not limited to TBI, stroke, AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS) and even aging [xx], although the etiology in each status could be rather distinct [21]. Vascular impairments induced by mTBI have been well documented both clinically in patients and preclinically in animal models, but the underlying mechanism has not been clearly understood. In the present study, we evaluated the microvascular injury, BBB disruption and pathologic changes in the astute/subacute phase in a rodent mTBI model, and compared with the sTBI model. We noted enlarged perivascular spaces surrounding blood vessels ipsilateral to mTBI every bit well as a pregnant increment in perivascular extravasation of plasma proteins, pericyte loss and reduced CBF. These data are indicative of a compromised cerebral microvasculature, equally well every bit a leaky and malfunctioning BBB. We then used the 5xFAD mouse model of AD to further clarify the link betwixt mTBI and AD, and found mTBI exacerbated BBB leakage, amyloid pathology and cognitive deficits post injury. In decision, our study demonstrated that mTBI induces BBB dysfunction, damages the perivascular basement membrane, and aggravates neuropathologies and cognitive deficiencies associated with Advertisement.

It is reported that mTBI induces relatively sustained shear stress located within a discrete region near the affect contact zone [43], which contributes to acute and/or subacute brain pathologies, including microvascular injury and BBB disruption [4]. Later, mTBI tin can elicit a complex sequence of cellular cascades, and lead to genomic responses and transcriptional changes in vascular cells [38], including vascular endothelial growth gene A (VEGFA), and compensatory changes in the extracellular matrix proteins and expansion of the basal lamina [37], which not only alter the basement membrane structure and perivascular space only also affect brain infiltration of peripheral leukocytes. Contempo evidence from RNA sequencing of encephalon endothelial cells in different animal models has demonstrated that similar vascular factor expression profiles exist among multiple neurodegenerative diseases including TBI [38], suggesting perhaps that the molecular signature of vascular damage might be common. Nevertheless, hereafter studies exploring vascular associated transcriptomic changes at single-prison cell level in both mouse models and human patients are necessary for defining the exact microvascular molecular signature in mTBI, and beyond.

There has been growing attention to mTBI and the development of dementia later in life [44]. Potential underlying mechanisms between TBI and afterwards evolution of AD include diffused axonal damage, persistent inflammation and vascular dysfunctions [5, 45]. While aberrant Tau pathology induced by TBI is considered a high-risk factor for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the production and accumulation of encephalon Aβ species are still considered equally the principal pathophysiological link between TBI and AD. Our study is the first to institute an mTBI model in 5xFAD mice and described the cognitive impairment and amyloid pathologies in the subacute stage following mTBI. Nosotros overserved that amyloid pathology and hippocampal dependent memory impairment was exacerbated within 8 days later on mTBI in 3–four months former 5xFAD mice when compared to the sham-operated group, which was largely consistent with previous studies using different transgenic models [46]. Aβ peptides are produced by neurons and other cell types, and they are afterward eliminated via several clearance pathways including receptor-mediated send across the BBB to the peripheral circulation, enzyme-mediated Aβ proteolytic deposition and removal by glial cells, and the perivascular drainage pathway for passive diffusion that connects to the meningeal lymphatic system [21]. Therefore, our data suggest that mTBI may alter the balance betwixt Aβ product and clearance in the brain.

The cerebrovascular system plays a central role in removing metabolic waste products and toxic proteins such as Aβ from the brain [20]. Equally Aβ homeostasis sustained by vascular clearance pathways are integrated functions of normal cerebrovascular structure and an intact BBB [21], the loss of vascular integrity could play a fundamental role in Advert pathogenesis, as well as the arbitration of tissue harm later TBI. While most current studies indicate to vascular injury after TBI, it remains unclear whether vascular impairment and BBB disruption induced by TBI affects the residuum between amyloid production and clearance in the brain, and atomic number 82 to cognitive impairment and dementia. Our study in 5xFAD mice demonstrated that mTBI exacerbates microvascular injury and BBB dysfunction in addition to existing vascular dysfunctions. Decreased BBB expression of amyloid receptors including Lipoprotein-related receptor protein ane (LRP1) and P-glycoprotein [42] have been previously reported in TBI rodent models, suggesting increased brain amyloid production and decreased transvascular clearance occur simultaneously after TBI. Furthermore, repetitive injury is a very important aspect of TBI, and the 2nd impact may elicit much stronger deficits in BBB, CBF and clearance. Thus, future studies are required to systematically determine the imbalance between Aβ production, perivascular drainage and transvascular clearance for a improve understanding of TBI-induced Aβ pathogenesis and increased risk for AD, and whether vascular-directed therapies to restore BBB integrity and clearance functions can reduce the risk of TBI-related neurodegenerative diseases. It volition be also interesting to examine the vascular impairment in repetitive settings and long-term furnishings on neurodegeneration, and compare the differential outcomes between immature and anile mice.

Decision

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that mTBI can induce BBB dysfunction and pericytes loss, impair the perivascular structure, exacerbate amyloid pathologies and cognitive decline in mice.

Availability of data and materials

The information that support the findings of this report are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- Ad:

-

Alzheimer's disease

- Aβ:

-

β-Amyloid

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BBB:

-

Claret–brain barrier

- CBF:

-

Cerebral blood flow

- CD13:

-

Cluster of differentiation xiii

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CTE:

-

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- DAPI:

-

4′,six-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DG:

-

Dentate gyrus

- DPO:

-

Days post operation

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- ISF:

-

Interstitial fluid

- LSCI:

-

Laser speckle contrast imaging

- LRP1:

-

Lipoprotein-related receptor protein i

- mTBI:

-

Mild traumatic encephalon injury

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- ROIs:

-

Regions of interest

- sTBI:

-

Severe traumatic brain injury

- TBI:

-

Traumatic encephalon injury

- TUNEL:

-

Last deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick stop labeling

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

-

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB et al (2018) NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer'southward illness. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc fourteen:535–562

-

Goate A, Hardy J (2012) Twenty years of Alzheimer'due south affliction-causing mutations: APP mutations later 20 years. J Neurochem 120:3–8

-

Association Alzheimer′south (2019) Alzheimer′s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement xv:321–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010

-

Sandsmark DK, Bashir A, Wellington CL, Diaz-Arrastia R (2019) Cognitive microvascular injury: a potentially treatable endophenotype of traumatic encephalon injury-induced neurodegeneration. Neuron 103:367–379

-

Blennow Grand, Hardy J, Zetterberg H (2012) The neuropathology and neurobiology of traumatic brain injury. Neuron 76:886–899

-

Wu Y, Wu H, Guo Ten, Pluimer B, Zhao Z (2020) Blood–brain barrier dysfunction in balmy traumatic encephalon injury: testify from preclinical murine models. Front Physiol 11:1030

-

Kenney Grand, Diaz-Arrastia R (2018) Risk of dementia outcomes associated with traumatic brain injury during military service. JAMA Neurol 75:1043–1044. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0347

-

Scott M, Ramlackhansingh AF, Edison P, Hellyer P, Cole J, Veronese M et al (2016) Amyloid pathology and axonal injury after brain trauma. Neurology 86:821–828

-

Yu F, Zhang Y, Chuang D-K (2012) Lithium reduces BACE1 overexpression, β amyloid accumulation, and spatial learning deficits in mice with traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 29:2342–2351

-

Furuya Y, Hlatky R, Valadka AB, Diaz P, Robertson CS (2003) Comparison of cerebral blood menses in computed tomographic hypodense areas of the encephalon in head-injured patients. Neurosurgery. 52:340–345 (word 345–346)

-

Menon DK (2006) Encephalon ischaemia afterward traumatic encephalon injury: lessons from 15O2 positron emission tomography. Curr Opin Crit Care 12:85–89

-

Wilson Fifty, Stewart W, Dams-O'Connor Thousand, Diaz-Arrastia R, Horton 50, Menon DK et al (2017) The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol 16:813–825

-

Corrigan JD, Hammond FM (2013) Traumatic encephalon injury every bit a chronic wellness condition. Curvation Phys Med Rehabil 94:1199–1201

-

Villalba N, Sackheim AM, Nunez IA, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT, Wellman GC et al (2017) Traumatic encephalon injury causes endothelial dysfunction in the systemic microcirculation through arginase-1–dependent uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Neurotrauma 34:192–203

-

Bhowmick S, D'Mello V, Caruso D, Wallerstein A, Abdul-Muneer PM (2019) Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 317:260–270

-

Foley LM, O'Meara AMI, Wisniewski SR, Hitchens TK, Melick JA, Ho C et al (2013) MRI assessment of cognitive blood flow later on experimental traumatic brain injury combined with hemorrhagic daze in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:129–136

-

Alluri H, Wilson RL, Anasooya Shaji C, Wiggins-Dohlvik Chiliad, Patel South, Liu Y et al (2016) Melatonin preserves blood-brain bulwark integrity and permeability via matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition. PLoS ONE 11:e0154427

-

Shi H, Wang H-Fifty, Pu H-J, Shi Y-J, Zhang J, Zhang West-T et al (2015) Ethyl pyruvate protects confronting blood-brain barrier damage and improves long-term neurological outcomes in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. CNS Neurosci Ther 21:374–384

-

Schwarzmaier SM, Zimmermann R, McGarry NB, Trabold R, Kim S-W, Plesnila N (2013) In vivo temporal and spatial profile of leukocyte adhesion and migration after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation 10:32

-

Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, Zlokovic BV (2015) Establishment and dysfunction of the claret-encephalon barrier. Prison cell 163:1064–1078

-

Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV (2019) Claret-brain bulwark: from physiology to disease and back. Physiol Rev 99:21–78

-

Dinkins MB, Dasgupta S, Wang Chiliad, Zhu G, He Q, Kong JN et al (2015) The 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer'southward affliction exhibits an age-dependent increase in anti-ceramide IgG and exogenous administration of ceramide further increases anti-ceramide titers and amyloid plaque brunt. J Alzheimers Dis JAD 46:55–61

-

Ojo J-O, Mouzon B, Greenberg MB, Bachmeier C, Mullan Yard, Crawford F (2013) Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury augments tau pathology and glial activation in aged hTau mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72:137–151

-

Romine J, Gao Ten, Chen J (2014) Controlled cortical touch model for traumatic brain injury. J Vis Exp JoVE 90:e51781

-

Zhang L, Schallert T, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q, Arniego P, Li Q et al (2002) A test for detecting long-term sensorimotor dysfunction in the mouse later focal cognitive ischemia. J Neurosci Methods 117:207–214

-

Lazic D, Sagare AP, Nikolakopoulou AM, Griffin JH, Vassar R, Zlokovic BV (2019) 3K3A-activated protein C blocks amyloidogenic BACE1 pathway and improves functional outcome in mice. J Exp Med 216:279–293

-

Wang Y, Zhao Z, Grub N, Rajput PS, Griffin JH, Lyden PD et al (2013) Activated protein C analog protects from ischemic stroke and extends the therapeutic window of tissue-type plasminogen activator in anile female mice and hypertensive rats. Stroke J Cereb Circ 44:3529–3536

-

Armulik A, Genové K, Mäe Thousand, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C et al (2010) Pericytes regulate the claret–brain bulwark. Nature 468:557–561

-

Dash PK, Zhao J, Kobori Due north, Redell JB, Hylin MJ, Hood KN et al (2016) Activation of Alpha 7 cholinergic nicotinic receptors reduce blood-encephalon bulwark permeability post-obit experimental traumatic encephalon injury. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 36:2809–2818

-

Winship IR (2014) Laser speckle contrast imaging to measure changes in cerebral claret flow. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ 1135:223–235

-

Lan X, Han Ten, Li Q, Yang Q-West, Wang J (2017) Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol 13:420–433

-

Nikolakopoulou AM, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Zlokovic BV (2017) Regional early on and progressive loss of brain pericytes but not vascular smooth musculus cells in adult mice with disrupted platelet-derived growth cistron receptor-β signaling. PLoS 1 12:e0176225

-

Miao W, Zhao Y, Huang Y, Chen D, Luo C, Su Due west et al (2020) IL-13 ameliorates neuroinflammation and promotes functional recovery after traumatic encephalon injury. J Immunol Baltim Md 2020(204):1486–1498

-

Libbey JE, Lane TE, Fujinami RS (2014) Axonal pathology and demyelination in viral models of multiple sclerosis. Discov Med xviii:79–89

-

Shlosberg D, Benifla M, Kaufer D, Friedman A (2010) Blood–encephalon barrier breakdown as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol vi:393–403

-

Obenaus A, Ng M, Orantes AM, Kinney-Lang E, Rashid F, Hamer Chiliad et al (2017) Traumatic brain injury results in astute rarefication of the vascular network. Sci Rep 7:i–14

-

Meng Q, Zhuang Y, Ying Z, Agrawal R, Yang X, Gomez-Pinilla F (2017) Traumatic encephalon injury induces genome-wide transcriptomic, methylomic, and network perturbations in brain and blood predicting neurological disorders. EBioMedicine xvi:184–194

-

Munji RN, Soung AL, Weiner GA, Sohet F, Semple BD, Trivedi A et al (2019) Profiling the mouse brain endothelial transcriptome in health and disease models reveals a core blood-brain barrier dysfunction module. Nat Neurosci 22:1892–1902

-

Hannocks M-J, Pizzo ME, Huppert J, Deshpande T, Abbott NJ, Thorne RG et al (2018) Molecular label of perivascular drainage pathways in the murine encephalon. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38:669–686

-

Thyboll J, Kortesmaa J, Cao R, Soininen R, Wang L, Iivanainen A et al (2002) Deletion of the Laminin 4 chain leads to dumb microvessel maturation. Mol Cell Biol 22:1194–1202

-

Yao Y, Chen Z-L, Norris EH, Strickland S (2014) Astrocytic laminin regulates pericyte differentiation and maintains blood brain bulwark integrity. Nat Commun v:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4413

-

Pop V, Sorensen DW, Kamper JE, Ajao Exercise, Murphy MP, Head E et al (2013) Early brain injury alters the blood–brain barrier phenotype in parallel with β-amyloid and cerebral changes in machismo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:205–214

-

Tagge CA, Fisher AM, Minaeva OV, Gaudreau-Balderrama A, Moncaster JA, Zhang 10-Fifty et al (2018) Concussion, microvascular injury, and early on tauopathy in young athletes afterwards impact caput injury and an impact concussion mouse model. Brain J Neurol 141:422–458

-

Fleminger S, Oliver DL, Lovestone S, Rabe-Hesketh Southward, Giora A (2003) Head injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: the prove 10 years on; a partial replication. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74:857–862

-

Ramos-Cejudo J, Wisniewski T, Marmar C, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, de Leon MJ et al (2018) Traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer's disease: the cerebrovascular link. EBioMedicine 28:21–30

-

Edwards G, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Soto C (2017) Amyloid-beta and tau pathology following repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 483:1137–1142

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the RWD Life Scientific discipline for profitable the Light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation Speckle Dissimilarity Imaging, Dr. Berislav Zlokovic and Dr. Yaoming Wang for guidance and technical support, and Dr. Zhonghua Dai for careful reading of the manuscript and critical comments.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R01NS112404 to Q.Yard., NIH grant RF1NS122060, the Alzheimer's Association (NIRG-xv–363387) and BrightFocus Foundation (A2019218S) to Z.Z.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

YW, HW and ZZ designed and performed experiments and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. JZ, SD, XX, XG, TG, SF and YY performed experiments. BP, XG, Forty, JFC, NSM, QM, and FGP contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments were canonical by the Institutional Beast Care and Use Committee at the University of Southern California per NIH guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary figures. Supplementary Fig. 1 Traumatic brain injury models with controlled cortical affect in mice. (A) The timeline for the establishment of the TBI mouse model and the other experimental procedures. (B) Brain precision impactor device (RWD Life Scientific discipline) to establish mTBI mouse model. (C-D) The experimental parameters used in the establishment of TBI mouse models. Supplementary Fig. 2 Neuropathological changes 3 days later sTBI or mTBI in mouse model. (A) Cerebral edema measured by brain water content. The injury significantly induced the development of cerebral edema at 24 hours mail service-injury in sTBI model compared to mTBI model. n = 8 mice per group, Data are presented as Hateful ± SD; ***, P < 0.001; NS, non-meaning (P > 0.05), ane-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni′due south mail-hoc tests. (B) Representative confocal images showing NeuN (green) staining and TUNEL assay (cherry) for apoptotic neuronal death in the impacted ipsilateral area after sTBI and mTBI, or sham-operation. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Quantification of the percentage of TUNEL-positive neuronal death in sTBI (due north = six mice) or mTBI (northward = 6 mice). Data are presented as Mean ± SD; *** P < 0.001 by Student′s t-test. Dash line indicates an boilerplate value from sham-operated group (n = iii mice). (D-E) Representative immunoblots (D) and quantification (E) of Synapsin I from the cortex in the injury ipsilateral side of sham-operated, mTBI and sTBI mice. β-Actin: loading control. Data are presented every bit Mean ± SD; n = 3 mice per group respectively; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni′south post-hoc tests. Supplementary Fig. 3 Neuroinflammatory changes three days afterward sTBI or mTBI in mouse model. (A) Representative images of fluorescence immunostaining for Iba1 (gray) and DAPI (blue), boxed regions show an activated and phagocytotic microglia (a1, a3) in the impacted ipsilateral side, and ramified microglia at resting state (a2, a4) in the contralateral side. Calibration bar in (A) 50 μm, in (a1-a6) ten μm. (B) Quantification for the pct of activated Iba1 positive cells (n = 6 mice per group) in the impact side (ipsi) and contralateral side (contra) in sTBI and mTBI mice (see method). Dash line indicates the boilerplate value from the sham-operated group (north = 5 mice). (C) Representative images of fluorescence immunostaining for GFAP (green) and DAPI (bluish), boxed regions (c1-c4) show astrocytes in the touch on side and the contralateral side. Scale bar in (C) fifty μm, in (c1-c6) x μm. (D) Quantification for the GFAP positive cells per mm2 (n = 6 mice per group) in the impact side (ipsi) and contralateral side (contra) in sTBI and mTBI mice. Dash line indicates the boilerplate value from sham-operated group (n = 5 mice). Information are presented as Hateful ± SD; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; NS, not-significant (P > 0.05) past past Student'southward t-test. Supplementary Fig. four Vascular damage in the subacute phase of mTBI in mice. (A-B) Representative images (A) and quantification (B) showing extravascular fibrin deposits in encephalon parenchyma 3 days subsequently mTBI. Lectin (gray), fibrin (reddish). northward = 7 mice; Calibration bar = 20 μm. (C-D) Representative images (C) and quantification (D) showing extravasation of intravenously administrated Alexa-555 cadaverine (blood-red) in encephalon parenchyma 3 days afterward mTBI. Lectin (greenish), northward = vii mice, scale bar = fifty μm. In B, D, data are presented as Mean ± SD; ***, P < 0.001 by Student'due south t-test. Dash lines indicate boilerplate value from sham-operated group (due north = 3 mice). (E-F) Cerebral blood flow reduction 3 days later mTBI. Representative laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) images (Eastward) and quantification of boxed regions (F) showing claret flow changes in the cortical regions 3 days later mTBI. Scale bar = fifty μm. Supplementary Fig. 5 The time grade of microglial activation after mTBI in mice. (A) Representative confocal microscope images showing Iba1-positive microglia cells (red) in cortex (CTX), Cornu Ammonis 1 (CA1) and dentate gyrus (DG) expanse 1-mean solar day, 3- and viii- days mail operation (DPO). Scale bar = 100 μm. (B-D) Quantification for the Iba1-positive microglia cells per mmii (n = 5 mice per fourth dimension signal) in CTX, CA1 and DG surface area 1 day, iii- and viii-days post operation (DPO). Information are presented as Hateful ± SD; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni'south mail service-hoc tests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Eatables Attribution four.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long equally you requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the article'south Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilize, y'all will demand to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/naught/ane.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Wu, H., Zeng, J. et al. Mild traumatic encephalon injury induces microvascular injury and accelerates Alzheimer-like pathogenesis in mice. acta neuropathol commun 9, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01178-vii

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01178-7

Keywords

- Traumatic brain injury

- Alzheimer'southward illness

- Microvascular injury

- Blood–encephalon barrier

- β-amyloid

Source: https://actaneurocomms.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40478-021-01178-7

0 Response to "what natural tbi h can you use to stain hardwood floors"

Postar um comentário